This report offers a concise, comprehensive, and critical overview of the empirical findings

available on the background and possible motivations of the young Western men and women who became jihadist foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. The findings were gathered from thirty-four reports and academic articles published between 2014 and 2019. The analysis addresses the data on demographic factors, economic and social marginalisation, past criminality, mental health issues, and the role of ideology and religion. The report summarises the findings, delineates the methodological limitations, and identifies some of the interpretive biases present on the existing work.

Methodology and Types of Studies and Data

This study is based on the empirical study that involves comprehensive literature review on Western foreign fighters. The focus is exclusively on English language papers on those who travelled (or tried to travel) from Western nations to Syria and Iraq to affiliate with jihadists groups engaged in the conflict. Lorne L. Dawson has examined studies published between 2014 and 2019. In reading the voluminous literature, I differentiated and collected studies that were substantially empirical in nature and focused on identifying who had left for Syria and Iraq and why. The studies examined are ones that base their conclusions on qualitative and quantitative data they collected, more than the views of various kinds of experts, commentators, and governments. Overall, though, the data covers fighters from Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and in a few instances, other non-European nations. Adequate discussion, with one partial exception of the large contingent of foreign fighters from the UK is noticeably missing, as is analysis of the even larger number from France.

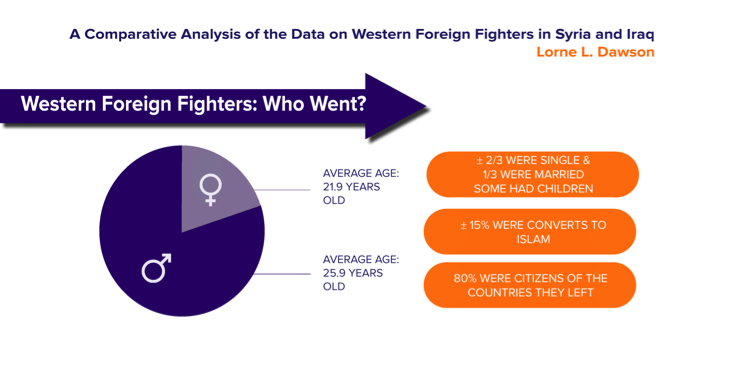

- Age and Gender: The ages numbers are consistent . Both the men and the women are young, and women are more younger. The median age has been 25.9. However, Dawson argues it is ambiguous whether the age cited reflects the age when the people cleared out to connect the jihad, were arrested, or indicted, or only reached for interviews, and the relationship of this date to the time at which they to begin with radicalised remains unknown.

- Marital Status: Only a handful of the studies report any information on the marital status of the foreign fighters. Dawson and Amarasingam report that most of their sample of twenty fighters were single, several were married and a few had children. El-Said and Barrett state that twenty-seven of their forty-three interviewees were single, fifteen married, and one divorced –but their sample includes individuals from four Muslim majority countries as well as three European Union countries. Rostami et al., and Marone and Vidino, working with more reliable government data, report respectively that ten of the forty-one Swedish fighters studied were married, and 60.8 percent of the foreign fighters from Italy were unmarried. Consequently, we can say little more about this characteristic of Western foreign fighters than not all of them are single, and biographical availability (i.e., relative freedom from social obligations), then, may only partially account for their willingness to travel and fight.

- Converts: Many have commented that converts are overrepresented in jihadist groups,37 but only nine of the thirty-four studies examined provide data on the number of converts in their samples. Converted to percentages the figures range from as high as 40 percent to as low as 6 percent. So while the data sources are variant, somewhat unreliable, and non-comparable (in any strict sense), the results support the supposition that converts are more susceptible to becoming foreign fighters (given the low figures for conversion to Islam in each of the countries

- Citizenship and Origins: It is widely thought that the vast majority of Western foreign fighters are from immigrant families, mainly from the 1.5 and 2.0 generations,40 and are citizens of the countries they have left. The data in the studies generally supports this conclusion, though it is surprisingly imprecise. Ahmed and Pisoiu say, for example, “virtually all the foreign fighters in our sample (97% vs 90%) are citizens of the respective countries” (i.e., UK and Germany). Helmuth says more vaguely that most of the 677 German nationals that left for Syria or Iraq “were considered German in the sense that they were either born in Germany, or spent significant time growing up in Germany (having moved to Germany before age 14)”.

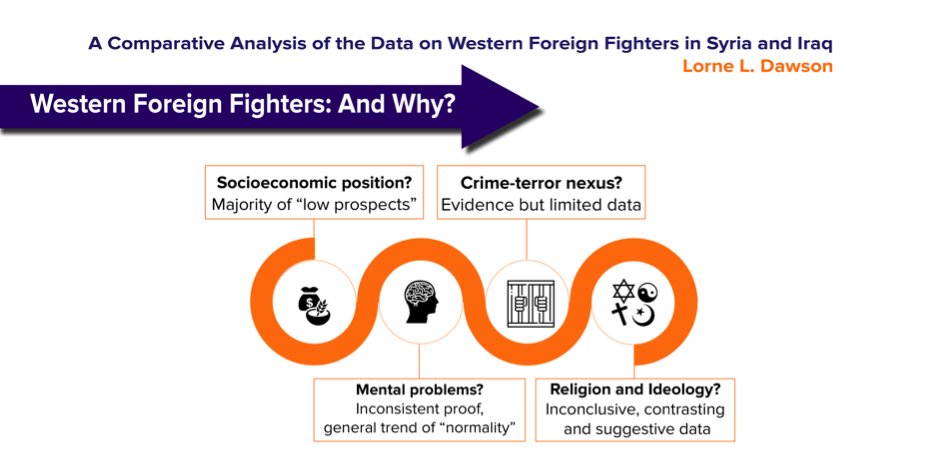

- Economic and Social Marginalisation: As many of the studies comment, scholars have been debating the relative significance of socioeconomic “push” factors in recruitment to jihadism for decades.49 Initially many assumed that poverty played a role in motivating terrorism, until several studies cast significant doubt on that assumption. Then for some years, it was widely assumed that economic factors were a poor predictor of radicalisation and terrorism. The research in hand, however, was inconsistent, and some scholars began to question that view. The empirical studies of Western foreign fighters emerged in the midst of this shift in perspectives, and on balance, these studies suggest that forms of social and economic marginalisation have influenced the mobilisation of foreign fighters, at least in Europe.

- Criminality: In referring to the crime-terrorism nexus, Basra and Neumann do not have in mind only the older alliances of convenience between criminal and terrorist organisations, such as the protection of heroin production in Afghanistan by the Taliban, but rather the convergence of criminal and terrorist “social networks, environments, or milieus.” They are interested in how “criminal and terrorist groups have come to recruit from the same pool of people, creating (often unintended) synergies and overlaps that have consequences for how individuals radicalise and operate.” Mounting evidence of the prevalence of criminal backgrounds amongst European jihadists drew their attention to the nexus, and some of the studies discussed in this analysis display an awareness of this issue

- Role of Ideology and Religion: Few aspects of the debate over the motivations of Western foreign fighters is as contentious as the discussion of the relative significance of ideology and religion. In most studies of foreign fighters, the issue is resolved implicitly by simply stressing the role played by other factors, either social psychological or socioeconomic. Nevertheless, two of the thirty-four studies addressed here clearly argue that the role of religion in motivating the foreign fighters is minimal. Five other studies appear to support this approach, but with varying degrees of ambiguity. Alternatively, four studies point to the primary role of religious motivations, and two others provide some ambiguous support for this view. Quite characteristically, Bergema and van San state “… the majority of jihadist fighters in [our] sample had an (folk) Islamic upbringing. Yet most did not actively practice Islam throughout their lives and showed a significant increase in religious devotion in the months prior to their departure”.

Conclusion

The results of this comparative analysis confirm views specialists have been expressing for some time. It is important, all the same, to provide a more comprehensive delineation, while documenting some of the strengths and limitations of the data which are as follows:

- The vast majority of Western foreign fighters were young men from Muslim immigrant families. The approximate average age of the fighters was 26 years, a bit higher than

Expected.

- About 18 percent of those who left were women and they were overall much younger, with an approximate average age of 21 years.

- The majority were single, but a sizable number, at least a third, were married and some had children.

- It is clear that most of the fighters were citizens of the countries in which they were living before leaving, something in the order of 80 percent. However, contrary to some expectations, the discrepancies in the data from country to country (e.g., Sweden and Italy) suggest that we cannot use this as an indicator of the relative integration of these young men and women.

- In Europe, the majority of the fighters came from the lower socioeconomic ranks of society, and as some observers have commented, they had “low prospects.” They had lower levels of educational attainment and experienced higher levels of unemployment.

The data, however, is inadequate and variable, and it does not seem to apply to foreign fighters coming from North America and to a lesser extent the United Kingdom. Lorne L. Dawson conclude that there is scarcity of research which is methodologically sound and comparable in nature. We need primary data in shape of interviews from ex, returning and emerging jihadists which will bring strong first-hand experience into the research and deeper conclusions

Amarasingam, Amarnath and Lorne L. Dawson. “‘I Left to be Closer to Allah’: Learning about Foreign Fighters from Family and Friends,” Institute for Strategic Dialogue (2018). Available at:

http://www.isdglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Families_Report.pdf

Ahmed, Reem and Daniela Pisoiu, “Foreign Fighters: An Overview of Existing Research and a Comparative Study of British and German Foreign Fighters,” Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg, (2014). Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.

El-Said, Hamed and Richard Barrett, “Enhancing the Understanding of the Foreign Terrorist Fighters Phenomenon in Syria,” United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism (July, 2017). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321184351_Enhancing_the_understanding_for_the_foreign_fighters_phenomenon_in_syria

Cook, Joana and Gina Vale. “From Daesh to ‘Diaspora’ II: The Challenges Posed by Women and Minors after the Fall of the Caliphate,” CTC Sentinel 12, no. 6 (July 2019): pp 30-45.

Coolsaet, Rik. “Facing the Fourth Foreign Fighter Wave: What Drives Europeans to Syria, and to Islamic State? Insights from the Belgian Case,” Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations (March, 2016). Available at: http://www.egmontinstitute.be/facing-the-fourth-foreign- fighters-wave/.

Corner, Emily and Paul Gill, “Is There a Nexus Between Terrorist Involvement and Mental Health in the Age of the Islamic State?” CTC Sentinel 10, No. 1 (2017), pp. 1-10. Dawson, Lorne L., Comprehending Cults: The Sociology of New Religious Movements. 2nd ed. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Dawson, Lorne L. “Trying to Make Sense of Homegrown Terrorist Radicalization: The Case of the Toronto 18,” in Paul Bramadat and Lorne Dawson, eds., Religious Radicalization and Securitization in Canada and Beyond. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014, pp. 64-91.

Dawson, Lorne L. “Discounting Religion in the Explanation of Homegrown Terrorism: A Critique,” in James R. Lewis, ed., Cambridge Companion to Religion and Terrorism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 32-45.

Dawson, Lorne L. “Sketch of a Social Ecology Model for Explaining Homegrown Terrorist Radicalisation,” The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT), Research Note 8, 2017. Available at: https://icct.nl/publication/sketch-of-a-social-ecology-model-for-explaining- homegrown-terrorist-radicalisation

Rostami, Amir, Joakim Sturup, Hernan Mondani, Pia Thevselius, Jerzy Sarnecki, and Chistofer Edling, “The Swedish Mujahideen: An Exploratory Study of 41 Swedish Foreign Fighters Deceased in Iraq and Syria,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 43, No. 5 (2020), pp. 382-395 (first published online version in 2018).

Vidino, Lorenzo and Seamus Hughes, “ISIS in America: From Retweets to Raqqa,” Program on Extremism, George Washington University, 2015. Available at: https://extremism.gwu.edu/ isis-america.