When entering the field of extremism studies, one is quickly overwhelmed by the sheer volume of publications produced each year. Recent political shifts across the globe are unlikely to reverse this trend, if anything, they have only accelerated it.

However, much of this academic and policy attention continues to focus on the far right and its derivatives, or on Islam-inspired extremism, particularly Jihadism. By contrast, the far left remains comparatively underexamined. This imbalance has serious implications, not least the persistent lack of insight into the role of women as active participants in armed political movements around the world.

As it turns out, far-left insurgencies stand out for their relatively greater gender balance. These movements often incorporate women not only as supporters or auxiliaries, but as fighters, commanders, and propagandists, reflecting their ideological commitments to egalitarianism and revolutionary participation. In contrast, far-right and religious extremist groups tend to be more explicitly male-dominated in their militant structures and symbolic representations.

In 2022, Alexandra Frénod and Caroline Guibet Lafaye published “On ne va pas y aller avec des fleurs”: violence politique – des femmes témoignent (“We’re Not Going in There with Flowers: Political Violence – Women Testify”). The book compiles testimonies from women who have experienced or witnessed politically motivated violence, as activists, victims, or observers, across different contexts and eras.

In a follow-up interview with Vice, the authors explored the presence of women within extremist movements. When asked specifically about armed far-left groups, they noted:

“Women generally make up a third of clandestine armed groups. They’re more rife in extreme left organisations, and in some national liberation groups, than in the extreme right or in political-religious organisations. How can this be explained? Far-left ideologies are based on emancipation and non-discrimination, so it’s logical that women would be interested in being part of them. They advocate equality between men and women on principle, which should theoretically result in the full participation of women in all political and military activities.”

Historically, that claim holds weight. Women have often taken on not just supporting, but leading roles in far-left militant movements, positions they were structurally excluded from in many right-wing or religiously inspired groups.

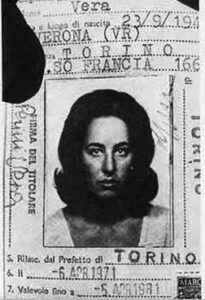

One such figure is Margherita Cagol – Mara, a key member of Italy’s Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades). Initially formed around squatting activism and labor agitation, the BR shifted rapidly toward armed struggle in the early 1970s. Between 1972 and 1975 – during the height of the Years of Lead (Anni di piombo), a period of political violence that spanned from the late 1960s into the 1980s – the group carried out a series of bombings, kidnappings, and assassinations. Cagol was central to this transition. She played a direct role in the BR’s turn to violence and helped shape its strategic orientation. In February 1975, she took direct part in a successful prison raid in Casale Monferrato, personally confronting guards at gunpoint to secure the release of Renato Curcio, her husband and one of the BR’s top leaders. Later that year, she orchestrated the kidnapping of businessman Vittorio Vallarino Gancia, heir to the Gancia winery, in an effort to finance further operations. The Sequestro Gancia, as it is known in Italian sources, ended in tragedy: in June, police located the hideout, and during the raid, Cagol was killed in a shootout, while an officer was severely injured. Gancia was rescued unharmed.

One such figure is Margherita Cagol – Mara, a key member of Italy’s Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades). Initially formed around squatting activism and labor agitation, the BR shifted rapidly toward armed struggle in the early 1970s. Between 1972 and 1975 – during the height of the Years of Lead (Anni di piombo), a period of political violence that spanned from the late 1960s into the 1980s – the group carried out a series of bombings, kidnappings, and assassinations. Cagol was central to this transition. She played a direct role in the BR’s turn to violence and helped shape its strategic orientation. In February 1975, she took direct part in a successful prison raid in Casale Monferrato, personally confronting guards at gunpoint to secure the release of Renato Curcio, her husband and one of the BR’s top leaders. Later that year, she orchestrated the kidnapping of businessman Vittorio Vallarino Gancia, heir to the Gancia winery, in an effort to finance further operations. The Sequestro Gancia, as it is known in Italian sources, ended in tragedy: in June, police located the hideout, and during the raid, Cagol was killed in a shootout, while an officer was severely injured. Gancia was rescued unharmed.

More recently, an analysis of 211 rebel movements active between 1979 and 2009 found that Marxist, Marxist-inspired, and other left-wing insurgencies had the highest prevalence of female fighters, in stark contrast to Islamist extremist groups, which severely suppressed female participation. In terms of high levels of female combatant involvement, leftist movements were up to eight times more likely than other ideological groups to exhibit such prevalence. For Islamist groups, the likelihood of women appearing in significant combat roles was virtually zero, with female participation, when it existed at all, almost exclusively limited to suicide bombing operations.

The trend extends across regions. In Latin America, women made up an estimated 40% of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and about 25% of the National Liberation Army (ELN) by the time of peace negotiations. Peru’s Shining Path was reported to have around 40% female active fighters, with women comprising half of its Central Committee.

This short text is far from an exhaustive analysis, however, it not intended to be one. Rather, it serves as an invitation to pursue further research into far-left movements, if for no other reason than to remind us that women can and do participate in political violence across a range of ideological frameworks, even if the extent and nature of their involvement vary widely from one movement to another.

References:

Alpert, Megan. “To Be a Guerrilla, and a Woman, in Colombia” The Atlantic (28 Sept 2016), https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/09/farc-deal-female-fighters/501644/.

Farinelli, Francesco, and Lorenzo Marinone. Contemporary Violent Left-wing and Anarchist Extremism (VLWAE) in the EU: Analysing Threats and Potential for P/CVE. (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, Radicalisation Awareness Network, 2021), https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-11/ran_vlwae_in_the_eu_analysing_threats_potential_for_p-cve_112021_en.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Felices-Luna, Maritza and Anouk Guiné (eds.) Género y conflicto armado en el Perú (Lima, Le Havre: La Plaza Editores & Groupe De Recherche Identités Et Cultures – Gric Université Le Havre Normandie, 2019).

Frénod, Alexandra, and Caroline Guibet Lafaye. “On ne va pas y aller avec des fleurs” : violence politique : des femmes témoignent. (Marseille : Hors-d’atteinte, 2022).

Hurlburt, Heather et al. “Policy Roundtable: How Gender Affects Conflict and Security” Texas National Security Review (27 Oct 2020), https://tnsr.org/roundtable/policy-roundtable-gender-and-security/.

Moretti, Mario, Rossanda Rossana, and Carla Mosca. Brigatte Rosse: Una Storia Italiana. (Milano: Baldini & Castoldi, 1998).

N.A. “El sufrimiento de mujeres combatientes y desmovilizadas.” Verdadabierta.com (27 Jan 2015), https://verdadabierta.com/testimonios-de-mujeres-exguerrilleras-que-desertaron-de-grupos-armados-ilegales/.

Uda, Gen. “The Far-Left Women Activists Picking Up Weapons.” Vice Media (24 Jan 2025), https://www.vice.com/en/article/far-left-women-who-choose-violence-interview/.

Wennerhag, Magnus, Christian Fröhlich and Grzegorz Piotrowsk (eds.). Radical Left Movements in Europe. (London and New York: Routledge, 2018)